A research paper in History is exactly what it says on the tin – a written endeavor to research some events, factors, situations or conditions in the past to prove a certain point. In this sense, it is rather close to a term paper, and indeed, the difference between the two is often vague.

The main distinctive feature is that a research paper isn’t tied to any particular period. You may have to write one over either a shorter or a longer period of time than a semester, and it may be larger or smaller than an average term paper, so you should adapt the following advice to the specifics of your particular task.

Choice of Topic

You may have a varying amount of freedom in your choice of topic. Sometimes the path is already decided for you by your professor, and the most you can do is to ask for a slight alteration. Sometimes you are given a free hand. Either way, you should strive to write about something you are both interested and well-versed in. One of the two can do, but try to avoid writing on topics that are both unfamiliar and boring to you. Remember, you will have to spend many hours gathering information and analyzing it, so don’t approach this choice lightly.

Laymen often perceive history as a mechanical record of events that happened in the past. The reality is much more complicated. History is not only concerned with what happened (although it is extremely important, and figuring out the nature of past events based on fragmented, incomplete and often biased sources is a major part of a historian’s work), but with why it happened and what were its consequences. At the same time, it isn’t the job of history to evaluate the moral nature of the events.

Any academic work is to a considerable degree based on existing bibliography on the subject. However, for History it is especially important as written sources are, by and large, all you have to rely on. You can’t run practical experiments, you can only glean some understanding from something somebody has written on the subject.

Therefore, your choice of topic is to a great degree based on the existing body of work on the subject. Ask yourself the following questions:

- Do scholars agree on your topic? If not, what is the point of contention? Do you consider the argument to be meaningful? Can you offer another approach to the problem?

- How well-researched is your topic? Are you the first to approach it in this particular way? Were there any recent findings that call for its reassessment?

- How much freedom do you have? Limitations aren’t always bad – when you are given a direction and a list of relevant documents to study, you already have something to build upon;

- Are there any assumptions about the topic that you and others take for granted? Are you sure these are correct?

- Will you have an opportunity to alter your choice later on, and if yes, to what extent?

In the end, your topic should deal with an interpretation of events, their causes and effects, be neither too general nor too narrow and, ideally, be something you would write about willingly. Here are some examples:

- Satsuma Rebellion: Reasons for Its Premature Start and Failure;

- Fall of Constantinople in 1453 And Its Immediate Influence on the European History;

- Erwin Rommel and His Role in the Plot Against Hitler;

- Intermarium Federation Proposal of Joseph Pilsudski and Its Potential Implications for The World History;

- Operation Overlord and Its Role In Bringing World War II To a Close.

Preparation and Research: Tips from Our Writers You Can’t Neglect

The first order of business is to prepare the sources you are going to use in your research. All sources can be roughly divided into two types:

- Primary – all the relevant materials created during the time period you research. This, however, doesn’t mean that they are the most useful and trustworthy: while people who wrote at the time the events in question took place have an advantage of seeing them play out in front of them, they don’t see them in perspective, are often biased and don’t possess complete information.

- Secondary – all the materials created after the time period in question. These are mostly analytical works that perceive the past events in perspective, see their connections with other factors and usually make a certain argument. You will mostly deal with such sources, and your own work will become such a source when you complete it.

As your time is limited, you should be very selective about the sources you use. Before choosing a work to use as a source, you should check how relevant and trustworthy it is. Find out the following:

- Who is the author? Is his background relevant for the problem in question? How objective he is likely to be? Is he biased? What is his reputation in academic community?

- When and where was the source created? Could these factors have influenced the author’s viewpoint (things like dominant views at the time, ideological constraints in the country of origin, limited information on the subject);

- What were the reasons for the creation of a source? Are they stated? Is it a scholarly work, a piece of propaganda, a work of fiction or art, or one of these things masquerading as another?

- How does the source look in the context of other sources on the subject? Does it represent a common point of view? Does it omit important pieces of evidence? If yes, can this omission be intended? Does it promote particular viewpoints?

Remember – a history research paper is only as good as the sources it is based on. Even if your reasoning and analytical abilities are impeccable, if they are based on disreputable, untrustworthy or one-sided sources, it immediately devalues your work.

Select a limited number of sources representing different points of view but unlikely to be strongly influenced by factors not related to the subject matter (politics, author’s views, etc.). Don’t try to encompass them all – even the narrowest subjects usually have enough sources to last you a lifetime.

When you start reading, know when to stop: don’t fall into the trap of reading for reading’s sake, for you can collect information and corroborative evidence indefinitely. Start writing when you feel you have an absolute minimum to work on, and read up on things that require additional attention as you go along.

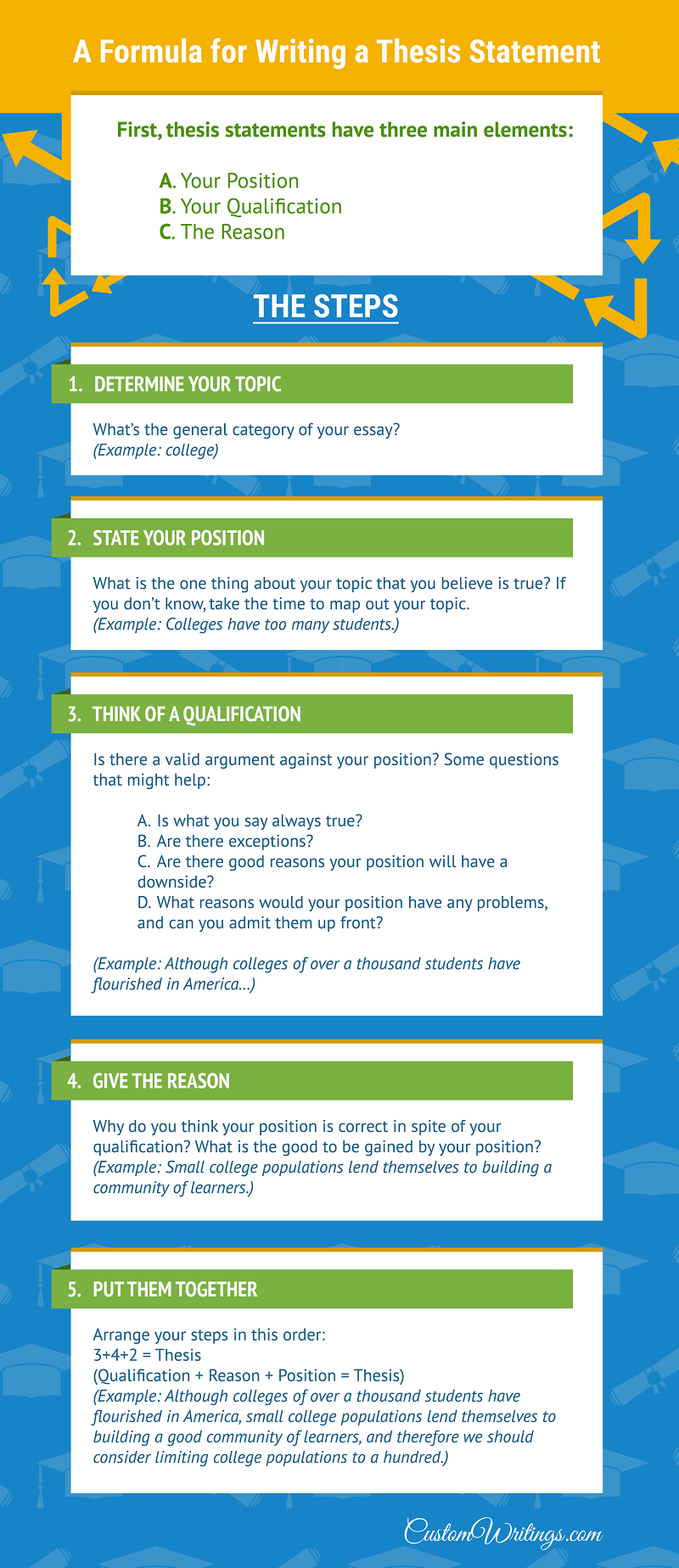

Outline/Thesis Statement

Once you’ve clearly formulated your topic and made about a third of the necessary research, you should start working on your outline. In the outline you are supposed to define the main points of your research, decide how they relate to each other and to the main topic of your work, in what order they are to be mentioned and what supporting details you should provide.

Remember – this isn’t a plan set in stone. It is an outline that you write mostly for your own convenience. If, in the course of your work, you find out that some facts are better mentioned in different order, or have unexpected similarities and connections and thus have to go hand in hand, make these changes. Right now, your paper is a work in progress.

Title

Once you’ve defined and narrowed down your topic, you won’t have particular problems with the title of your paper. A history research paper doesn’t need its title to be overly creative and unusual – its main purpose is to clearly and unequivocally denote the topic and, if possible, your main argument. Consult your instructor if you feel any doubts.

Body Paragraphs

This is where most of your work lies, and it is where you should start after you finish preliminary work. Introduction comes later, possibly last, when you already know how your research turned out.

In writing the main part of your paper, it is important to follow certain conventions. They may differ in different colleges, but some things are accepted almost everywhere:

- Use of past tense. As everything related to your subject matter by definition happened at some point in the past, this is the tense you should use. If you’ve carried out the habit of sometimes falling into “literary present” from your creative writing course or somewhere else, forget about it – it does not belong here.

- Analyze the events of the past in context of what happened next, but don’t fall into the mistake of viewing them from the position of a modern human. Remember that the people you are writing about lived in another time, in completely different conditions and shared sets of values and assumptions completely different from those of your generation. Today, some of these values may seem quaint, barbaric or alien, but at the time they were quite natural. Analyze but do not judge.

- Use formal, academic voice. Don’t use informal words, expressions and sentence structures. Avoid passive voice. Don’t use first and second person pronouns.

- Use a consistent citation style. Find out the format your college uses, get your hands on a style guide and start using it from the very beginning. It will save you a lot of time later on.

- Avoid general statements. Whatever people may say, history is an exact science. Don’t make sweeping statements. If you know the year, say it. If you know the number, mention it. If you don’t, make no assumptions.

- Don’t rely on quotes too much. A paper that has too many quotes looks as if you don’t have anything of your own to say. You should use quotations only when it is absolutely necessary. Paraphrase in all other cases. Employ your own writing and analytical skills when possible.

Introduction and Conclusion

Once you’ve finished with the main body of research, you can write an introduction based on it. Point out the main topic of your paper, what arguments you intend to make, what conclusion you expect to draw and so on.

To a considerable degree, it is a formal part built around the main part of the paper, and it is exactly the reason why you should start working on it when everything else is already done – otherwise you will have to rewrite it multiple times to reflect the changes your research underwent in the course of work.

Conclusion mostly recounts the same ideas as introduction does, only now you mention whether research went as planned, whether you achieved the expected results, what you believe to be the significance of your research, what work remained undone and what can be done in the future.

Editing and Proofreading

Check everything you’ve written so far. Correct any grammar, syntax and spelling mistakes you could have made. You can use online spellcheckers for that purpose, but don’t expect much from them – the best course of action would be to hire a professional editor or proofreader.

- Check the facts. You could’ve made a mistake when quoting somebody, or used incorrect notes or something else – the larger the amount of data you had to deal with, the higher the likelihood of errors is.

- Go through the paper with the style guide in hand once again. The rule of formatting and quoting may seem trivial and unimportant for you, but academic community has different views on the subject.

- Refine your text. This means eliminating all informal expressions and structures (like contractions), repetitions, filler words (like “the fact that”, “in order to”, “as a matter of fact”, “somewhat”, “fairly”, “considerably”) and overly complex sentences. If you have a long and complex sentence, either break it up or remove parts of it completely – chances are, you can say the same things in a much simpler way. Don’t try to sound smart and sophisticated by using long, multi-clause sentences. If a 6-syllable word has a 1-syllable synonym, use the shorter variant.

- Give your paper to a trustworthy person to read and review. They can point out many mistakes that eluded you throughout the process of writing.

If necessary, don’t hesitate to correct, revise and even rewrite parts of your paper. Even if you find flaws at such a later date, it is better to spend some additional time on corrections than to hand it in as it is and hope nobody would notice.